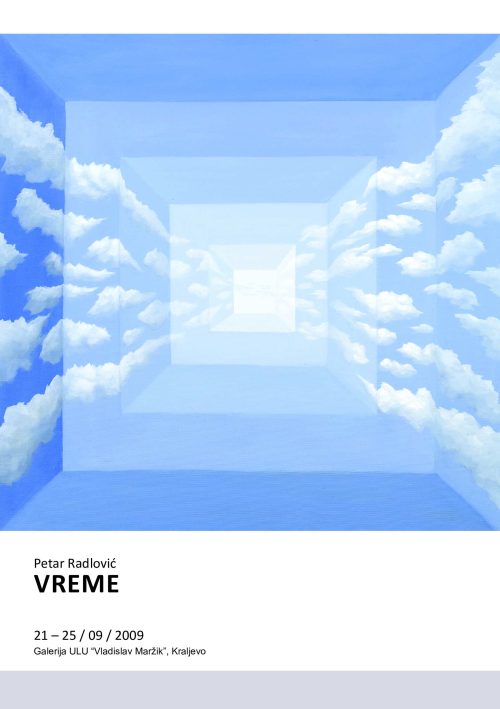

VREME

Vreme, ono atmosfersko koje se smenjuje iz kiše u sunce, preko magle do snega, i vreme kao prolaznost, dve su teme koje se u slikama Petra Radlovića stapaju u jednu, jer prvo je slika drugog: ono što prolazi, ali se i ciklično vraća, jesu te atmosferske promene koje sugerišu promenu uopšte, ali i prolaznost koja, mada deluje zanemarljivo u ovakvom poimanju kružnog vremena, zaprema ne mali deo samog tog kruženja.

Na Radlovićevim slikama nema ljudi, ali se čovek stalno oseća kao izopšten iz te večnosti cikličnog; oseća se kao njen svedok i kao neko ko trpi od njene krutosti i neuključivosti, jer je baštinik linearnog trajanja, onog konačnog iz koga ga samo delimično izbavlja melanholičan pogled na ono beskonačno koje mu je, i otud melanholija, nedostupno.

U trenucima kada ta melanholija postane svesna sebe, prerasta u strah, jer večnost je dostupna samo pogledu, i to pogledu kroz žaluzine zatvorenog prozora. U nekom drugom poglavlju vremena vedro nebo kao da obećava i čovekov udeo u njemu, kao da ga upija u sebe, ali dokle – to pitanje uvek preostane.

Tu su i trenuci međuvremena, maglovite nejasnosti kada izgleda da nam ništa nije uskraćeno, ali se oseća i strepnja jer ništa nije ni zagarantovano. Postoje još i oni povlašćeni komadići vremena kada nas neka mena u prirodi obuhvati i nakratko učini delom svog obilja, i zato su zalasci sunca opšte mesto svih umetnosti.

Pokušaj učestvovanja u večnosti najčešće, ipak, omane i ostavi čoveka na njegovom usamljenom postamentu, s kojeg je, doduše, dobar pogled, ali koji stoga nije manje usamljen. Ostaje nejasno da li svetlost izvire iz tog pogleda kao projekcija željenog ili iz onoga što se zaista vidi, kao putokaz i zov za biće koje misli i oseća, poznaje i očekuje.

Dragana Popović

TIME

Weather, as atmospheric conditions changing from rain to sun, through mist to snow, and time as transience constitute two themes that, in the paintings of Petar Radlović, merge into one—the former being the representation of the latter. That which passes but also returns in cycles are those atmospheric changes, suggesting change in general as well as transience which, though seemingly irrelevant within such an understanding of cyclic time, occupies no small part of the cycles themselves.

In Radlović’s paintings there are no people, yet the human presence is always palpable as one excommunicated from the eternity of cycles—seen as its witness, as one who suffers from its rigidity and lack of inclusiveness, being the heir to the linear permanence of the finite, and only partly saved by a melancholic glance toward the infinite, inaccessible to him and thus the source of melancholy itself.

In moments when this melancholy becomes aware of itself, it develops into fear, for eternity is accessible only to the gaze—the gaze through the jalousies of a closed window. In some other chapter of time, however, the clear sky seems to promise a human share in it, as if absorbing him into itself, but until when? That question always remains unanswered.

There are moments of intertime as well—misty vaguenesses when it appears that nothing is denied to us, yet anxiety is present because nothing is guaranteed. There are also favored fragments of time when a change in nature overtakes us and briefly makes us part of its abundance; this is why sunsets are a common place in all the arts.

Nevertheless, the attempt to participate in eternity most often fails, leaving the human being on his lonely pedestal, from which, admittedly, the view is good, but which is no less lonely for that reason. It remains unclear whether the light emerges from that view as a projection of desire or from what is truly seen—as a road sign and a call intended for a being who thinks, feels, knows, and anticipates.

Dragana Popović